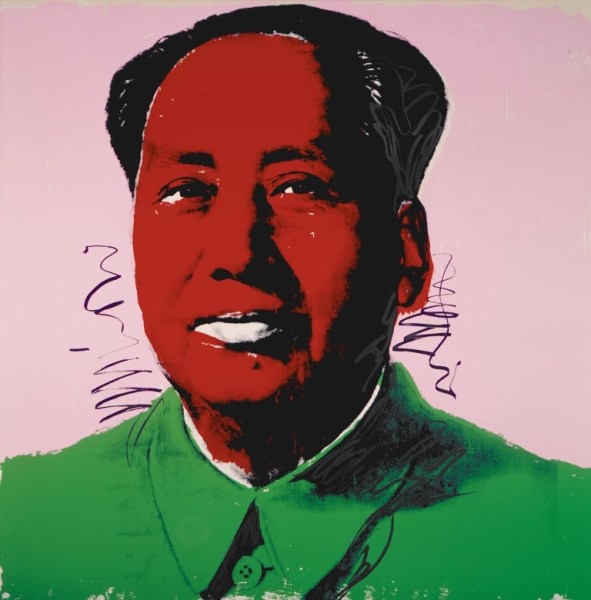

Andy Warhol, Mao, 1972.

1784: The First US Representatives go to China: Arriving in Guangzhou, the Empress of China is the first vessel to sail from the U.S. to China. On board is Samuel Shaw, who was appointed as an unofficial consul by the U.S. Congress. He is unable to gain diplomatic recognition for the U.S., but this journey marks the new nation’s entrance into the lucrative China trade in tea, porcelain, and silk.

1796: The Macartney Mission: Lord George Macartney becomes the first Western diplomat to journey to Beijing in an effort to establish direct diplomatic relations with the Chinese imperial court. He receives a rare audience with the emperor, but his effort to initiate a commercial agreement between Britain and the Middle Kingdom is unsuccessful.

1810: The Opium Trade begins: British merchants begin to smuggle Indian opium into China. Seeing that this raises their profit margins, most American firms follow suit.

1830: The First American Protestant Missionaries arrive in China: The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions sends the first two American missionaries to China: the Reverends Elijah Bridgman and David Abeel. Bridgman will be one of the first Americans to undertake the study of China’s history and culture, and will also write a history of the U.S. in Chinese.

1834: British East India Company is disbanded: Once holding a monopoly on the China trade, the British East India company loses its charter in 1834, and the trade at Guangzhou opens up to other traders, including American merchants.

The Chinese authorities destroy 1,000 tons of opium seized from British merchants at Humen in 1839.

1842: The Treaty of Nanking: The British forces come out victorious of the First Opium war, which began in 1839, and force the Qing government to sign the Treaty of Nanking. The treaty ends the existing system of trade through officially licensed merchants, opens 5 new treaty ports to trade, including Shanghai, grants most favored nation status to Britain, gives it control of Hong Kong, and grants British citizens immunity from local law. The treaty will serve as the model for future treaties between China and other Western nations.

1844: The Treaty of Wangxia: in 1843, Secretary of State Daniel Webster sends Caleb Cushing to China as Minister Plenipotentiary to negotiate a treaty with the Qing. The terms include extraterritoriality for U.S. citizens in China and most favored nation status. This marks the beginning of official diplomatic relations between the U.S. and China.

1847: The Coolie Trade Begins in the New World: The first ship carrying Chinese labourers, known as “coolies,” arrives in Cuba with workers for the sugar plantations. Soon thereafter, coolie traders begin to dock at U.S. ports.

1848: The California Gold Rush and Chinatown: The Gold Rush and the construction of the transcontinental railroad draw large numbers of Chinese workers, escaping bad harvest and famines in their home country. They work in mines, on railroads, and perform other menial tasks, and start gathering in the first Chinatowns, notably in San Francisco, the oldest in the U.S.

1850-1864: The Taiping Rebellion: A rebel movement erupts in southeastern China which costs millions of lives and ends up almost completely separating northern from southern China for a decade. The Qing ultimately manage to suppress the rebellion, thanks in part to the assistance of American soldier-of-fortune Frederick Townsend Ward and other foreigners, but the dynasty is weakened and will never fully recover.

Two children crossing a street in San Francisco’s Chinatown (late 19th century). Photo by Arnold Genthe.

1858: The Treaties of Tianjin: The Second Opium War sparked off by British and French forces the Qing government to sign new treaties with several foreign powers, including the U.S. The treaties open more ports to foreign trade and settlement, allow the establishment of permanent diplomatic legations in Beijing, grant additional trading privileges to foreign merchants, legalize the opium trade, give missionaries the right to proselytize throughout inland China and open its rivers to foreign warships. The U.S. acquires the same privileges as Britain and France under the terms of most favored nation status. In 1860, frustrated with Qing delays in the implementation of the treaties, British and French forces march on Beijing and destroy the imperial Summer Palace on the city’s outskirts.

1867: The Rover Incident: Taiwanese aborigines attack shipwrecked American sailors, killing the entire crew, and then defeat the retaliatory expedition by the American military. Some Americans advocate for the annexation of the island, but the plan does not come through.

1872: The First Official Delegation of Chinese Students come to the U.S.: Yung Wing, a naturalized U.S. citizen who received a degree from Yale University in 1854, formed the Chinese Education Mission in 1870 with approval and support from the government of China. The program intends to train Chinese to work as diplomats and technical advisors to the government. In 1872, he brings a group of 30 students from China to the U.S. to live and study there. The Qing end the program in 1881, due to rising anti-Chinese sentiment in the U.S., fears that the students are becoming too Americanized, and frustration that they are not being granted the promised access to U.S. military academies.

1875: First Restrictions on Chinese Immigration: The U.S. Congress passes the Page Act, which bars entry for Chinese laborers and women brought in for prostitution. The law is the first in a series of increasingly restrictive acts targeting Chinese immigration.

1878: First Chinese Legation established in the U.S.: China establishes a diplomatic mission in Washington, D.C. This marks the beginning of full bilateral ties between the U.S. and China.

“What Shall We Do With Our Boys”: anti-Chinese caricature by George Frederick Keller for ‘The San Francisco Illustrated Wasp‘ (3 March 1882)

1882: The Chinese Exclusion Act: Congress passes the Chinese Exclusion Act, which suspends Chinese immigration to the U.S. for 10 years. There are approximately 300,000 Chinese in the U.S. at the time, up from 25,000 in 1852.

1885: Anti-Chinese Violence breaks out: In the 1870s, racist violence erupts across the American west, culminating with the Rock Springs massacre, when a mob launches a vicious attack against Chinese miners in Wyoming in September 1885, killing at least 30 people.

1892: Geary Act: The Chinese Exclusion Act’s prohibition on Chinese immigration is extended for another ten years, and all Chinese and Chinese descendants in the U.S. are required to carry residence permits or face deportation.

1894-95: First Sino-Japanese War: Japanese and Chinese forces clash over influence in Korea, and Japan comes out victorious. As part of the settlement, Japan takes control of Taiwan, Manchuria and the vassal state of Korea, and also gains new privileges in China including the right to build factories. The U.S. gains this right as well, through the most favored nation principle, but must now face greater competition from Japan in Southeast China.

1899-1900: The Open Door Notes: In September 1899 and July 1900, Secretary of State John Hay issues the two Open Door Notes to all foreign powers with interests in China to warn them not to threaten the free trade system in the area and take advantage of a weakening China to carve it up as they did with Africa. This is the first clear and official statement of U.S. China policy.

1900: The Boxer Uprising: A nationalist, anti-imperialist movement, calling itself the Society of Right and Harmonious Fists and referred to by Westerners as the Boxer Rebellion, begins in late 1899, targeting all foreigners as well as Chinese Christian converts. The uprising reaches a peak in the summer of 1900 when Boxer forces march on Beijing, with the support of the Qing court. For two months they occupy the capital and besiege the foreign legation district. Eventually, a multinational force including U.S. marines based in the Philippines lifts the siege and crushes the Boxers, looting the city and forcing the Qing to submit to a punitive settlement that bankrupts the government.

1902: The provisions of the Geary Act are extended and expanded: The Chinese Exclusion Act’s prohibition on Chinese immigration is extended for ten more years.

1905: Anti-American Boycotts in China: After the U.S. and China fail to come to an agreement on a new immigration treaty in 1904, Chinese in Shanghai, Beijing, and other cities launch boycotts of U.S. products and businesses.

Concessions and spheres of influence in China in 1910.

1911: The Fall of the Qing Dynasty: The Qing enact a range of constitutional and economic reforms, but an uprising breaks out in the inland city of Wuhan in October, and within a few months local rebellions take place throughout the country. These lead to the fall of the dynasty.

1912: Founding of the Republic of China: On January 1, Sun Yat-sen, leader of the Nationalist Party, Kuomintang, becomes president of the newly created Republic of China, which the U.S. immediately recognizes. Sun’s Revolutionary Alliance has widespread support, but power lies with regional militaries, and within a few months he must step down in favour of General Yuan Shikai.

1915: Japan’s 21 Demands: After entering World War I on the side of the Allies, Japan seizes German territories in Shandong Province. It then issues 21 demands to the Chinese Government, seeking extensive new trade and territorial privileges. President Woodrow Wilson objects to these demands, and the U.S. advises the Chinese to resist as long as possible.

1917: China Enters the Warlord Period: Yuan Shikai, who had himself proclaimed Emperor in 1916, passes away. China fragments into territorial fiefdoms ruled by warlords, with a nominal national regime located in Beijing. The U.S. maintains diplomatic relations with the central government, but U.S. citizens and companies in China deal directly with local leaders.

1919: The Treaty of Versailles and the May 4 Incident: China joined the Allies in World War I, partly at President Wilson’s urging, and hoped that in return it would regain control over the former German concessions that Japan seized. However, this hope is not fulfilled by the Treaty of Versailles, as Japan, Britain, and France secretly agreed to give those territories to Japan permanently. On May 4, students gather for a demonstration at the Tiananmen in Beijing, and then storm the house of a pro-Japanese minister.

1921: The Chinese Communist Party is founded: In July, a small group of Chinese leftists meet in the French Concession in Shanghai to form the Chinese Communist Party. Within a couple of years, the C.C.P. forges a united front with Sun’s Kuomintang.

1922: The Washington Conference Agreements: under the pressure of the U.S., the Japanese-held areas in Shandong are returned to Chinese sovereignty.

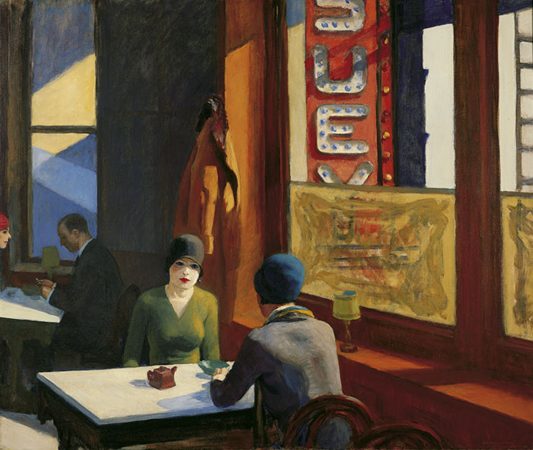

Chop Suey. Painting by Edward Hopper (1929)

1924: The Immigration Act is extended: Also known as the National Origins Act, this law places stringent quotas on new immigrants based upon their country of origin and enacts a total prohibition on new arrivals from China and Japan, with a few exceptions, such as students and high-skilled professionals.

1925: Sun Yat-sen dies: Chiang Kai-shek emerges as Sun’s successor to lead the Nationalist Party, and the next year he launches the Northern Expedition to reunite China from the party’s base in Guangzhou. He finally succeeds in 1928, when Nationalist forces claim Beijing.

1927: Nationalist Capital established: After bringing most of southern China under their military control, the Nationalists establish their capital in Nanjing.

1927: End of the United Front: Chiang Kai-shek launches a major purge of Communists in Shanghai, forcing them into hiding in the countryside: the two parties remain in a state of civil war for the next 20 years.

1928: The U.S. formally recognizes the Nationalist Government: The U.S. becomes the first nation to recognize the new regime as the legitimate government of China.

1931: Manchurian Incident: Rogue elements in the Japanese Army stage an explosion on a rail line outside the city of Shenyang, which they then use as a pretext for a military takeover of Manchuria. The following year, they install the last Qing Emperor, Puyi, as ruler of the puppet state of Manchukuo. The U.S. and the League of Nations denounce Japan’s manoeuvre and calls for the restoration of Manchuria to Chinese control. As a result, Japan leaves the League of Nations in 1933.

Mao Zedong during the Long March, in 1937.

1934: The Long March: After a prolonged period of fighting and encirclement around their base in the mountains of southern Jiangxi Province, a group of Communists break through the Nationalist lines and commence a search for a new base of operations. After wandering for more than a year, they end up in Yan’an, in Shaanxi Province in north central China, where they remain for the next decade. Along the way Mao Zedong solidifies his predominance over the party and army.

1937: The Second Sino-Japanese War: After a clash at the Marco Polo Bridge outside of Beijing, a full-scale war begins between the Chinese and the Japanese. The Japanese forces defeat the Chinese troops in Shanghai and push inland, with their assault reaching a destructive peak in the Rape of Nanjing in November. Just before the Japanese overrun the capital, the Nationalist Government flees inland to the city of Chongqing, where it remains for the duration of the war. 20 million Chinese are killed, and American public opinion overwhelmingly supports China. President Roosevelt offers China financial and military aid.

1938: Pearl S. Buck wins the Nobel Prize for literature: Born in the U.S. but raised in China, Pear Buck is rewarded for her fictional work located mostly in China and which greatly popularizes Chinese culture in the U.S., notably The Good Earth (1931).

1941: Pearl Harbor: On December 7, Japanese forces attack Pearl Harbor, and the US formally enters into the war on China’s side.

Eleanor Roosevelt and Soong May-ling in front of the White House in 1943.

1943: Madame Jiang Jieshi visits the U.S.: Chiang Kai-shek’s American-educated wife, Song Meiling, comes to the U.S. to rally support for China’s war effort. In a show of solidarity, the U.S. pushes to have China declared a major power in any post-war settlement, and also promises that China will gain sovereignty over all areas seized by Japan, especially Manchuria and Taiwan.

1943: The End of Extraterritoriality and Exclusion: China and the US sign a treaty ending 100 years of extraterritoriality in China. Simultaneously, the U.S. passes legislation allowing Chinese immigration for the first time in 60 years, although it is still under a very low quota.

1944: The Dixie Mission: A U.S. Army Observation Group goes to the Communist base camp at Yan’an to explore the possibility of U.S. aid to Communist forces, but nothing comes out of it, due mostly to Chiang Kai-shek’s objections.

1945: Japan Surrenders: After the nuclear bombings on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9, as well as the Soviet invasion of Manchuria on August 8, Japan surrenders. With the common Japanese enemy gone, Nationalists and Communists let their long-simmering disputes erupt again. In December, President Harry S. Truman sends General George Marshall as a Special Envoy to negotiate a cease-fire a cease-fire and a national unity government between the two sides, but in vain: full-scale civil war begins in early 1946. Marshall later testified that he soon realized the Communist forces were far superior to the Nationalists and if the U.S. supported the latter, it would have been dragged into a costly war it did not want to fight.

1947: The Wedemeyer Mission to China: President Truman sends General Wedemeyer to China on a special mission to assess the current conditions in China’s civil war. Wedemeyer returns with recommendations for large-scale aid to the Nationalists. Although a strong U.S. “China lobby” supports this position, many in the Truman administration see the Nationalists as a lost cause.

1948: The China Aid Act: The Truman administration extends additional aid to Chiang Kai-shek’s regime but refrains from getting deeply involved in the civil war. By the end of the year, the Nationalists suffer a series of defeats, and a Communist victory seems more and more likely.

1949: The People’s Republic of China is founded: After driving the Nationalists from the Mainland, Mao Zedong proclaims the establishment of the P.R.C. on October 1. Before this, American ambassador John Leighton Stuart meets with Communist leaders to discuss recognition of the P.R.C., but the talks fail when Mao announces his intention to lean towards the side of the Soviet Union. Meanwhile, Chiang Kai-shek and his troops flee to Taiwan, where they form the exiled Republic of China government in Taipei, i.e., Taiwan. The Truman administration recognizes the R.O.C. as the sole legitimate government of China, helping it retains its seat on the U.N.’s security council, with veto power, and announces the U.S. will defend the island from any attack. Yet, anti-communist organizations like the American China Policy Association and leaders like Senator Joseph McCarthy ask the question “Who Lost China?”, and blame the Truman administration for the “avoidable catastrophe” of having allowed a new Communist power to be born.

American Marines running past the body of an enemy soldier on the Korean Peninsula, September 1950. Photo by David Douglas Duncan.

1950: The Korean War: The Soviet-backed North Korean People’s Army invades the U.S.-supported South Korea on June 25. The U.N. and the U.S. rush to South Korea’s defense. The U.S. leads a U.N.-backed offensive against North Korea and pushes it back north of the 38th parallel, the initial border between the two countries. However, when the U.N. troops approach the Chinese border, Beijing’s forces retaliate and force them back down to the 38th parallel. The Korean War – or, as it is called in China, « the war to resist the U.S. » – lasts for three years and ends with a stalemate, killing 3.5 million people, including 400,000 Chinese and 40,000 American soldiers. A divided Korea becomes an important factor in U.S.-China relations thereafter and the whole region turns into a theatre of ideological struggle and military tension. In China, anti-American sentiment rises and almost all remaining U.S. citizens have pulled out by 1954.

1954: First Taiwan Strait Crisis: Chiang Kai-shek’s Republic of China deploys thousands of troops in the Taiwan Strait in August. China’s People’s Liberation Army responds by shelling the islands. The Eisenhower administration moves the U.S. fleet to protect Taiwan, and thereafter guarantees it economic and military aid until 1979. The same year, delegates from around the world meet in Geneva to resolve the Indochina War between France and Vietnam. Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai attempts to shake hands with Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, who refuses to acknowledge him.

1955: The Formosa Resolution: The US Government confirms its commitment to defend Taiwan.

1956: The Sino-Soviet Split begins: The differences between Mao’s China and the U.S.S.R. become more pronounced when Khrushchev denounces Stalin, who died three years before, in his Secret Speech. Mao responds with a condemnation of Khrushchev. By 1960, the U.S.S.R. has recalled its last scientific and technical advisors from China and cut off all assistance.

1958: The Second Taiwan Strait Crisis: The P.R.C. shells Nationalist outposts on islands off the coast of Fujian Province, forcing the U.S. to again intervene by sending ships into the Taiwan Strait.

1958: The Great Leap Forward: Mao launches a mass campaign to reform society and increase industrial output in a very short period of time, by organizing the countryside into massive communes that are expected to produce food, iron and steel. Devastating famines ensue, and rural production of iron and steel in “backyard furnaces” do not meet the targets for industrial production, leading to the near collapse of the Chinese economy by 1962. More than 30 million people are estimated to have died due to this, along with at least 2 million people killed while attempting to rebel against the government.

The Dalai Lama flees from China and finds refuge in India in 1959.

1959: Tibetan Uprising: A widespread rebellion begins in Lhasa, Tibet, in March. Thousands die in the ensuing crackdown, and the Dalai Lama flees to India. The U.S. joins the U.N. in condemning Beijing for human rights abuses, while the C.I.A. helps arm the Tibetan resistance.

1960: Eisenhower Visits Taiwan: President Eisenhower becomes the first U.S. head of state to pay an official visit to a Chinese government when he meets with Chiang Kai-shek in June.

1964: China’s first Atomic Test: In October, China conducts its first test of an atomic bomb. The test comes amid U.S.-Sino tensions over the escalating conflict in Vietnam. Chinese engage in mass demonstrations accusing the U.S. of imperialist actions. Later documents reveal that President Johnson considered pre-emptive attacks to halt China’s nuclear program but found the move too risky.

1965: The Immigration and Naturalization Act: The U.S. puts an end to the long-standing system of quotas based upon national origin, and opens the doors to more migrants from Asia. Chinese immigration from Taiwan and Hong Kong soars in the following years.

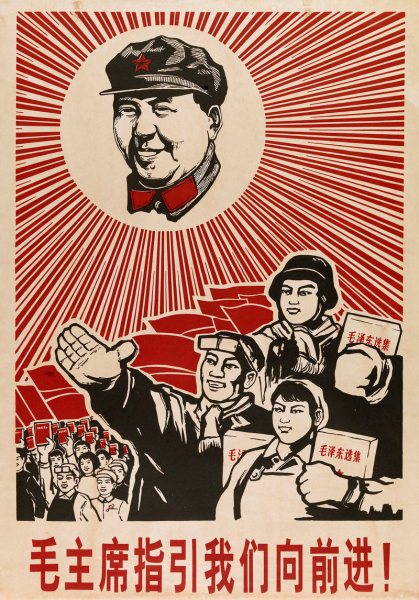

‘Chairman Mao leads us Forward’: Cultural Revolution propaganda poster (1968)

1966: The Cultural Revolution: Mao launches the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, unleashing a decade of mass-mobilization, purges, lynchings and massacres. Bands of student-aged Red Guards are at the vanguard of the movement, which quickly descends into chaos. In 1967, a group of radicals take over and temporarily shut down the Foreign Ministry, forcing the P.R.C.’s foreign relations to a halt for several months. By 1968, Beijing has reined it the worst excesses, and it controls the urban chaos by sending urban youths to the countryside for re-education. The death toll of the Cultural Revolution is uncertain, varying from the hundreds of thousands to 20 million.

1968: The Tet Offensive: Backed by China since 1962, the North-Vietnamese and the Vietcong launch a stunning counter-offensive against American troops in Vietnam. The anti-war movement in the U.S. gains strength, and President Johnson begins to explore possibilities for withdrawing from Vietnam. In the fall, Richard Nixon is elected president, partly on the strength of his claim that he will get the country out. 60,000 American troops will eventually die in the war.

1969: Sino-Soviet Border Conflict: Sino-Soviet tensions lead to skirmishes over the Siberian border in March: 91 Soviets and 30 Chinese are killed. The conflict incites the Nixon Administration to forge an alliance with the P.R.C. against the Soviet Union. Behind the scenes, Nixon’s National Security Adviser, Henry Kissinger, starts working towards a “rapprochement” with Beijing.

Time magazine’s April 1971 cover on the US’s ping-pong team visit to China

1971: Ping-Pong Diplomacy: In the first public sign of warming relations between Washington and Beijing, China’s ping-pong team invites members of the U.S. team to China in April. They and the journalists accompanying them are among the first Americans allowed in China since 1949. In July, Henry Kissinger makes a secret trip to China and meets with Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai to prepare for President Nixon’s visit to China the following year. Shortly thereafter, the U.S. recognizes the P.R.C., endowing it with the permanent Security Council seat that had been held by Chiang Kai-shek’s Republic of China since 1945. In the U.S., hard-line anti-communists denounce Nixon’s policy of rapprochement, but public opinion supports the move. In China, several left-wing leaders also complain about the rapprochement, including Lin Biao, the head of the military, but he dies in a mysterious plan crash while trying to defect to the U.S.S.R.

1972: Nixon visits China: In February, President Nixon spends eight days in China, becoming the first American head of state ever to set foot on the Chinese mainland. He meets with Mao and signs the ‘Shanghai Communiqué’ with Zhou Enlai, officialising the improvement of U.S.-Sino relations.” The visit initiates a period of “détente” during the Cold War. In China, the rapprochement with the U.S. also makes it clear that it now considers the Soviet Union its chief adversary.

1974-76: Changes in Leadership: President Nixon resigns from office in the wake of the Watergate scandal, while in China, Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai decline in health. Two years later, both pass away.

1977-78: The Rise of Deng Xiaoping: In China, Deng Xiaoping, Zhou Enlai’s protégé, becomes de facto leader of the P.R.C. despite the opposition of the party radicals. In the U.S., Jimmy Carter, the new president soon sends Secretary of State Cyrus Vance and National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski to China to re-start negotiations on normalization.

1979: Formal Ties between China and the U.S.: President Carter grants the P.R.C. full diplomatic recognition and officially acknowledges the ‘One China principle,’ i.e., that Taiwan is part of China, while the P.R.C. accepts that the U.S. can carry commercial and cultural contacts with Taiwan: since then, the R.O.C. is to be referred to as ‘The Republic of China on Taiwan’. Meanwhile, the U.S. Congress passes the Taiwan Relations Act, which guarantees Taiwan military support. This initiates the US’s ‘strategic ambiguity’ regarding China and Taiwan.

1980: Deng Xiaoping’s Four Modernizations: To boost China’s stagnant economy, Deng Xiaoping embarks on a series of economic reforms (including modernizations in agriculture, manufacturing, technology and defense), and starts opening the country’s doors to foreign investment and business. Four special economic areas are opened in the south, three of them in the province of Guangdong, including Shenzhen. Companies from the U.S., Europe and Japan flock to China. China also joins the I.M.F. and the World Bank. The same year, New York City and Beijing become sister cities.

1982: The Third Communiqué and Six Assurances: The US and China release a joint communiqué in August in which the U.S. agrees to reduce its arms sales to Taiwan and China agrees to emphasize a peaceful resolution of the Taiwan issue. Meanwhile, the Reagan administration also offers “six assurances” to Taiwan that it will continue to support the island and its government.

1983: One Country, Two Systems: Deng Xiaoping proposes the “one country, two systems” approach for reunification with both Hong Kong and Taiwan. The same year, the U.S. State Department changes its classification of China to « a friendly, developing nation ».

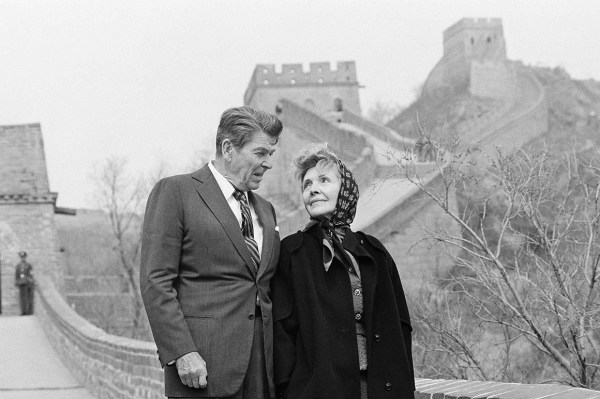

President Ronald Reagan and First Lady Nancy Reagan visit the Great Wall north of Beijing, in April 1984.

1984: Reagan visits China: President Reagan visits China in April; in June, the U.S. government allows Beijing to make purchases of U.S. military equipment.

1985: Xi Jinping’s first visit to the U.S.: Mr Xi visits Iowa as leader of a five-man agricultural delegation and is invited to stay in Muscatine with a local family.

1986: China joins Multilateral Institutions: China joins the Asian Development Bank and applies for membership in the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and the World Trade Organization.

1988:The Peace Corps enters China: China allows the U.S. Peace Corps to begin sending volunteers to China. The first group arrives in China to teach English in 1992.

1989: The Tiananmen Square Massacre: Thousands of students hold demonstrations in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square, demanding democratic reforms and an end to corruption. On June 3, the government sends in military troops to clear the square, leaving hundreds of protesters dead. In response, the U.S. imposes economic sanctions on China and puts an end to weapons exports. The Communist Party’s General Secretary, Zhao Ziyang, is blamed for his support to the student movement, and is replaced by Jiang Zeming. Mr Jiang accelerates the country’s transition towards a “socialist market economy”.

1990: The first McDonald’s in China: American fast-food chain McDonald’s opens its first restaurant in mainland China in Shenzhen. In April 1992, it opens another one in Beijing, which becomes the largest in the world, with 700 seats: the restaurant serves 40,000 customers on its opening day.

19992: The End of History: The American political scientist Francis Fukuyama publishes his landmark essay The End of History and the Last Man, predicting the universalization of Western liberal democracy after the fall of the Soviet Union.

1993: The Clash of Cvilizations: The American political scientist Samuel Huntington publishes his landmark essay “The Clash of Civilizations?” in the journal Foreign Affairs, arguing that people’s cultural and religious identities will be the primary source of conflict in the post-Cold War era, and predicting that the rise of the “Confucian Sinic civilization” is one of the most significant, long-term threats to the West.

1994: The Fugitive: « The Fugitive, » starring Harrison Ford, becomes the first foreign film to be released in the People’s Republic of China.

1995: Taiwanese President visits the U.S.: President Bill Clinton grants a visa to Taiwan President Lee Teng-hui so that he can enter the country as a private citizen to attend a reunion at his alma mater, Cornell University. Beijing protests vehemently and recalls its ambassador.

1996: The Third Taiwan Strait Crisis: Just before Taiwan’s first free presidential elections, the P.R.C. conducts military exercises and ballistic missile tests in the Taiwan Strait, to intimidate voters against re-electing the Nationalist Party’s, pro-independence candidate, Lee Teng-hui. In response, President Clinton orders the U.S.S. Nimitz, a nuclear-powered aircraft carrier, and her attendant battle group to the waters off Taiwan, forcing Beijing to stop the missile tests. Lee Teng-hui eventually wins the election comfortably, and the incident incites Beijing to launch a 25-year rearmament plan.

Front page of ‘The New York Times’ on July 1, 1997.

1997: The Hong Kong handover: Beijing officially regains sovereignty over Hong Kong, promising to preserve the former British colony’s democratic system for the next 50 years. In the fall, Jiang Zemin visits the U.S., the first state visit to the U.S. of a Chinese paramount leader since 1979.

1999: Bombing of the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade: In May, N.A.T.O. accidentally bombs the Chinese embassy in Belgrade during its campaign against Serbian forces occupying Kosovo, killing three and wounding twenty, and shaking U.S.-Sino relations. The U.S. and NATO offer apologies, but protests erupt throughout China, targeting official U.S. property, including the embassy in Beijing. Tensions ease after an apology from President Clinton and the visit of a special envoy to Beijing. The same year, U.S.-China relations are also damaged by accusations that a Chinese-American scientist at the Los Alamos National Laboratory has given nuclear secrets to Beijing.

1999: The Macau handover: Beijing officially regains sovereignty over the island of Macau, promising to preserve the former Portuguese colony’s political system for the next 50 years.

2000: Normalized Trade Relations: in October, President Clinton signs the U.S.-China Relations Act of 2000, granting Beijing permanent normal trade relations with the U.S. and paving the way for China to join the World Trade Organization in 2001.

2001: The Hainan Island Incident: In April, a U.S. reconnaissance plane collides with a Chinese fighter, killing its pilot, and makes an emergency landing on China’s Hainan Island. The 24-member US crew are detained for 12 days, until President George W. Bush expresses regret over the incident. The same year, two Chinese citizens die during the 9/11 terrorist attacks on American soil. Facing trouble of its own with Muslim terrorism in Xinjiang, the P.R.C. offers public support for the U.S.’s War on Terror and for the coalition campaign in Afghanistan. A long-term counter-terrorism dialogue begins between the two countries, while the Bush administration permanently shifts its strategic focus from East Asia to the Middle East.

2005: Making China a “Responsible Stakeholder”: In September, Deputy Secretary of State Robert B. Zoellick calls on China to serve as a “responsible stakeholder” and use its influence to draw nations such as Sudan, North Korea, and Iran into the international system.

2006: North Korea’s First Nuclear Test: One year after walking away from talks aimed at curbing its nuclear ambitions, North Korea conducts its first nuclear test. China, however, serves as a mediator to bring Pyongyang back to the negotiating table.

The 2008 Olympics’ opening ceremony in Beijing.

2008: The Beijing Olympics: Beijing hosts the 29th Olympic Games, the most expensive Olympiad in history. It uses the event to showcase its rapid development, modernization and power, and ends up with the highest tally of gold medals, with twelve more than the U.S.

2008-10: The Financial Meltdown and China’s economic rise: While the global system collapses and the U.S. enters the Great Recession, China’s economy soars and it surpasses Japan as the world’s second-largest economy in 2010; the same year, it triumphantly hosts the World Expo in Shanghai.

2009: The B.R.I.C.S.: Chinese president Hu Jintao takes part in the first summit of the B.R.I.C.s (Brazil, Russia, India, China and then South Africa) in June, in Yekaterinburg, Russia. In the context of the Great Recession, the B.R.I.C.S. gradually evolve into an alternative international association of economic powers to the U.S.-led G20. In November, President Barack Obama visits Hu Jintao in Beijing to discuss economic concerns, nuclear proliferation and climate change; this is the first time a U.S. president visits China during his first year in office.

2009: The Ürümqi riots: Anti-Chinese rioting erupts in the capital of the Xinjiang Uyghur region in northwestern China, killing some 200 people, and leading to a brutal crackdown, the mass internment and “re-education” of Uyghurs in the region in the following decade.

2011: The US ‘pivots’ toward Asia: In an essay published in November in the journal Foreign Policy, U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton outlines a US “pivot” to Asia, calling for “increased investment—diplomatic, economic, strategic, and otherwise—in the Asia-Pacific region” so as to counter China’s clout. The same month, at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit, President Barack Obama announces the U.S. and 8 other nations have reached an agreement on the Trans-Pacific Partnership—a multinational free trade agreement.