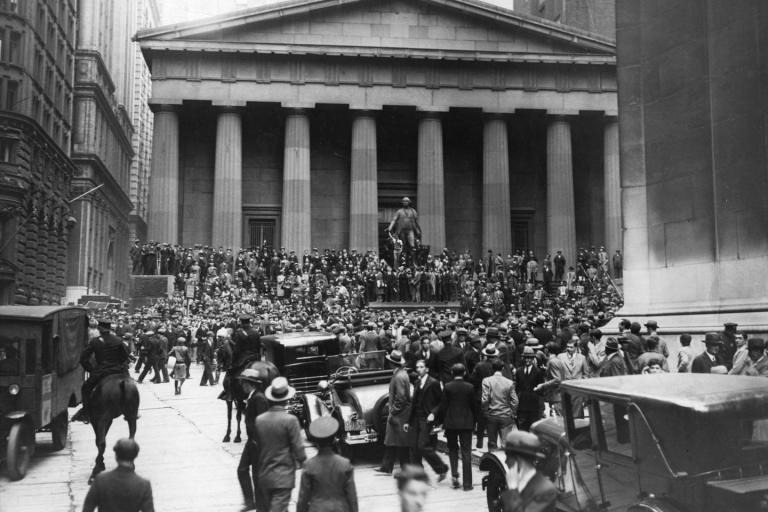

Crowds gather outside the New York Stock Exchange during the Wall Street Crash of 1929

Global financial crises are far from being a rare event – the IMF actually counts 124 of them between 1970 and 2007 – but the Great Recession that began in 2008 was the worst since the Wall Street Crash of October 1929 which had sparked off the Great Depression.

The collapse of the American stock market between Black Thursday (October 24) and Black Tuesday (October 29) came as a surprise to much of a country that was still riding high on the consumerism triumphant of the Roaring Twenties. The annual production of cars had trebled, reaching a record-breaking 6 million (Ford alone producing 9,000 of its cult Model Ts a day). Radios, washing machines, hoovers, refrigerators – you name it: Americans were simply rushing to buy new conveniences, most of them on credit. The elite maximized their profits: in 1928, there were 40,000 millionaires in the country, against just 7,000 in 1914. Banks prospered: by 1929, the combined balance sheets of the country’s 25,000 lenders reached $60 billion.

Ford Model T advertisement in the 1920s

Yet, a lot of this prosperity turned out to be a more bubble. By 1929, the ‘real’ economy was suffering from problems ranging from agricultural overproduction to sluggish steel production and construction; even car sales were going down. Inflation was worryingly low, household debt soared, and yet financial speculation thrived.

The Fed did not react until the late 1920s, and eventually decided to raise interest rates from 3.5% to 5% in 1928 to slow markets, rather than lower them to boost the economy. This was a fatal mistake: the increase did not at all temper share prices – on September 3, 1929, the Dow Jones Industrial Average reached a historic 381 points – but it did hurt America’s flagging industries even more.

More bad news from abroad. In September, the London Stock Exchange crashed when Clarence Hatry, a fraudulent financier, and his associates were arrested. Panic took over the New York Stock Exchange. The sell-off was huge: on October 29 alone, the Dow Jones lost close to 25%; by November 13, it was at 198, down 45% in two months. By 1932, the financial losses had reached $30b, more than ten times the federal budget. Some 11,000 banks went bankrupt between 1929 and 1933, starting with banks in agricultural states like Arkansas, Illinois and Missouri, and then reaching cities in industrial states like Chicago, Cleveland and Philadelphia.

Front page of the Daily Express the day after Black Thursday

The protectionist policies of the administration made things even worse for the whole of the economy. On June 17, 1930, President Herbert Hoover, a Republican, signed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act into law, which massively raised tariffs on agricultural imports and manufacturing goods. Unsurprisingly, the U.S.’s trading partners responded to this act of trade war by introducing tariffs on their own on American goods: exports from the US plummeted by 60% from 1930 to 1933. Meanwhile, the Fed failed to play its role as leader of last resort. When the crisis started, it did bring temporary respite to the financial system by buying government bonds, but soon withdrew from active operations, and on March 14, 1933, as the crisis peaked, it actually closed its doors: this became the worst week in the history of American finance, no less than 2,000 banks closing once and for all.

The whole economy was affected. Industrial production was divided by 50%, unemployment rose from 2 million to 15 million in 1933 (i.e., from 3.2% to 25% of the working population), and at least 2m people became homeless (out of a population of 125 million).

Migrant Mother during the Great Depression (1936). Picture by Dorothea Lange

In the 1932 presidential campaign, Herbert Hoover’s Democratic opponent, Franklin D. Roosevelt, castigated the erratic choices of his administration and of the Fed. Once elected, his administration aimed at reviving the ailing economy, notably through a massive injection of publicly supplied capital (i.e., $1 billion) in the 6,000 of the remaining 14,000 banks. Just as the UK had done as early as 1931, the US also abandoned the gold standard in April 1933. Most of all, the administration sought to “de-risk” the financial system itself. To do so it both reinforced the powers of the Fed and made it more dependent on the executive branch; it created new regulators like the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Federal Deposit Insurance Commission (FDIC), which protected $2,500 of deposits per customer in case of a bank failure; and in 1933, the Democratic-led Congress passed the Glass-Stegall act, which separated commercial and investment banks, and banned banks receiving consumer deposits from engaging in risky activity – two pillars of financial regulation which kept the financial system relatively safe, stable and compartmentalized until 1999.