Hasta la visa

The Economist, October 15, 2016

The government is foolishly making life harder for foreign students

“They are not, and never have been, immigrants.” So declared Enoch Powell of international students in an infamous speech against migration in 1968. Ending up to the right of Powell, who was as fierce a critic of immigration as they come, is an uncomfortable position. But that is where Theresa May’s government finds itself with respect to overseas students. As part of a plan to reduce the number of migrants, on October 4th Amber Rudd, the home secretary, announced new restrictions on foreign students, including tougher entry requirements for those going to lower-quality institutions. The proposal is merely the most recent attempt to deter foreigners from paying tens of thousands of pounds to study in Britain.

Since the turn of the century the number of foreign students in Britain has more than doubled. In contrast to Britain’s overall immigration trend, growth has come not from Europe but from the rest of the world. Chinese students are by far the biggest group, numbering 89,540 last year, up from 47,740 in 2004. The steep fees paid by non-EU citizens have made higher education an important British export. By one estimate foreign students contribute £7 billion ($8.6 billion) a year to the economy in fees and living expenses.

Yet in the past few years the growth has stalled. To find out why, visit any student common room. An American PhD student at Cambridge University complains that acquiring a visa for her doctorate was more onerous than when she studied in Britain a decade ago. This time she had to list every trip she had taken outside America since the age of 18. Applicants have to prove they have more money than they used to: £9,135 in the bank plus their tuition fees, up from £7,380 last year. And the government has introduced an annual “immigration health surcharge” of £150. The doctoral student says she gets e-mails almost weekly from the university citing new requirements it faces with regards to its foreign students.

The government has also removed provisions that allowed students to stay on after graduation to seek work. In 2012 it abolished a visa which allowed those who had completed degrees in Britain to remain in the country for two years without the firm offer of a job. The withdrawal of this perk put off many South Asian students, thinks Ruth Owen Lewis, director of the international office at Aberystwyth University. The number of Indian students, which soared from 14,625 in 2004 to 39,090 in 2011, has fallen to 18,320 since then.

The recent rhetoric may exacerbate this trend. Following Ms Rudd’s announcements, one Indian newspaper advised those considering studying in Britain to revisit their plans. Others see it differently: William Vanbergen, head of BE Education, a consultancy in China that advises those wishing to study abroad, says that some Chinese parents imagine that Brexit will mean fewer refugees and terrorists sneaking into Britain, making the country less dangerous for their offspring.

Other countries spy an opportunity. Australia and Canada, popular alternatives for Asian students seeking an English-language education, offer (limited) chances to stay and work, making them attractive destinations. Australia has simplified its student visa system to boost its appeal. Germany is offering more courses in English. And since 2014 public universities there have largely abolished tuition fees, including those for foreigners. This month the Irish government revealed plans to encourage more foreign students. “Everybody is doing the exact opposite to us,” laments Ms Owen Lewis. While the number of foreign students in Britain has stalled, in other countries it is zipping up. In Australia it increased by 11% last year.

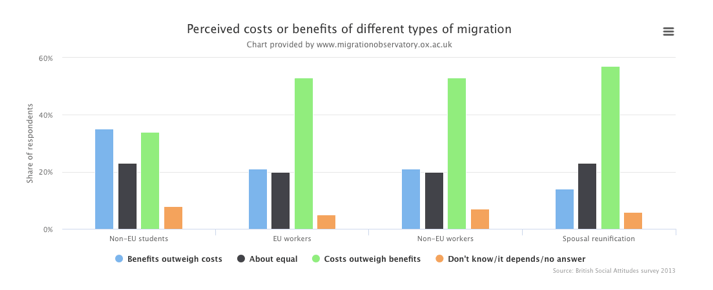

Nor does the crackdown look politically necessary. A YouGov poll last year found that students were the most popular group of migrants among voters, three-quarters of whom thought their numbers were about right or should be higher. Even supporters of the right-populist UK Independence Party were keen on them. Reducing immigration in general will hurt Britain’s economy; barring fee-paying students is a particularly damaging way to do it.

Food for thought on the situation of overseas students in the UK

International students represent approximately 35% of all migrants in the UK today (alongside 50% of economic migrants and 15% of people migrating on the basis of family reunification rights). [1] These foreigners represent around 20% of all students in the UK, a vast majority of them studying at university (80%), while the rest enrol at tertiary institutions (8%), independent schools (7%) and English language schools (1%).

As a whole, the UK has the second highest number of international students in the world (10% of the whole) after the US (19% of the whole).

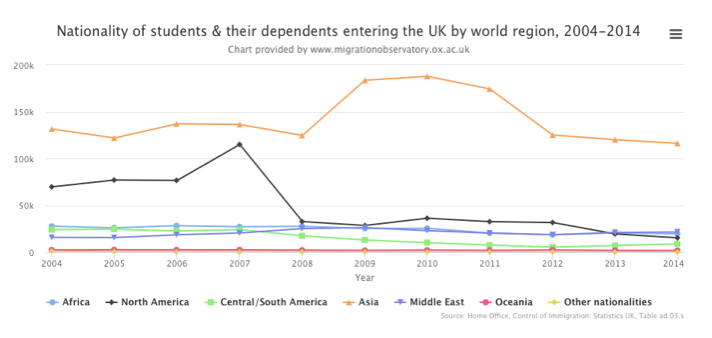

As can be seen in the chart below, the greatest number of students is by far from Asia, especially from China [2].

The reasons for this attractiveness are that the UK has a long tradition of intellectual and academic excellence, a powerful network of cultural and diplomatic influence worldwide, and, most of all, it boasts some of the best universities in the world, which draw some of the most promising young international brains for fees which, on average, remain far cheaper than their American counterparts, though they are allowed to make overseas students outside the EU pay higher fees than the cap of £9,000. [3]

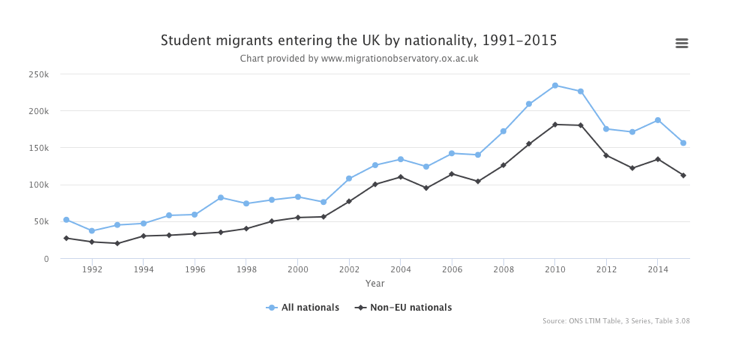

Yet, the numbers of new arrivals have diminished sharply from a peak of 234,000 in 2010 to 156,000 in 2015, and the totals have stalled around 450,000 today (i.e., 130,000 EU nationals and 320,000 non-EU nationals).

This is the result of the policies enforced to, somewhat desperately, reduce net immigration to the UK to « the tens of thousands » since 2010. Indeed, international students have been one of the rare categories the Cameron and the May governments have actually been able to reduce, while the total number of refugees admitted in the country was already limited, and a majority of both spousal reunion migrants and, most of all, economic migrants are from the EU and have kept increasing.

To achieve its aims, the Cameron government started by cracking down on applicants it suspected of trying to abuse the system by using a study visa as a quick ticket to the British job market and tracked down schools granting bogus sponsorships for study visas. [4] Most of all, it abolished visas allowing students a two-year work permit in the UK after completing their degrees at a British university. [5] Additional measures included reducing the numbers of hours international student could work and raising language requirements for students at further education colleges. Under the May government, applicants have been subjected to additional hassle, they have been required to have more substantial financial resources and to pay an extra £150 each year by means of an “immigration health surcharge”.

This crackdown on international students has not been particularly popular, even among a population increasingly hostile to foreigners. Indeed, surveys like the British Social Attitudes have shown that, along with high-skilled migrants, international students are the category that Britons disapprove of the least, compared to low-skilled labour migrants, spousal reunion migrants, and asylum seekers.

The Conservative government’s policy on overseas students has thus appeared to be driven by ideology and political expediency rather than common sense. Indeed, not only are overseas students good business, pumping as they do between £7 and £10 billion a year into the economy, but draining the best brains from around the world makes them the bridge-builders of tomorrow (as politicians, researchers, artists, diplomats or executives) and priceless contributors to the UK’s soft power. Conversely, the closing of the UK’s academic gates threatens to send a message of parochialism if not hostility to the rest of the world, and is being taken advantage of by competitors.

The situation has become even more troubling since the Brexit vote. Since June 2016, there have been additional concerns regarding what will happen with EU students already in the UK or planning to go there in the future, whether quotas will apply to them, whether they will still be entitled to loans, whether their fees will increase above the £9,000 cap that had applied to them too… Afraid that the Brexit vote will further damage their reputation abroad, British universities themselves have been particularly worried that foreign scholars and lecturers might be reluctant to take jobs in the UK, which would be catastrophic for higher education there, given how dependent on talented European scholars it has become: in 2016, of the academics teaching and researching at British universities, no less than 55,000, or 30%, were foreigners, two thirds of whom (32,000) were from the European Union. British universities have also expressed their concerns about the future of frameworks such as the ERASMUS programme by which they are structurally connected to other European ones, but also the EU’s funding for research, from which they benefit disproportionately.

Unsurprisingly, a vast majority of British academics opposed Brexit: in a poll conducted prior to the June 2016 vote by Times Higher Education, nine in ten university staff actually said they would vote to Remain.

[1] There is a difference, however, between EU nationals, who are more likely to be economic migrants (64%, against 20% of students), and non-EU citizens, who are far more likely to come to the UK for study (50%) or family reasons (21%) than economic ones (25%).

[2] A greater and greater number of them (i.e., around 25%) are from mainland China, and are more affluent than those that used to come from Hong Kong. Many of these students tend to stay on in well-paid jobs, notably in the financial sector, and typically the Sunday Times rich list is now peppered with a few Chinese names, like Yan Huo, the founder of Capula, a hedge fund, or Ning Li, the boss of Made.com, a furniture website. It must be added that young Britons of Chinese origin already living in the UK also happen to be the best pupils in the country. For instance, in 2015, in GCSE exams, taken at 16, 77% achieved five good grades, slightly more than Indians (72%) and way above the national average of 57%. Even more impressive, among those on free school meals 74% achieved the same standard, while the national average was 33%. Unsurprisingly, the entry rate to university of these British pupils of Chinese origin is 58%, by far the highest of all ethnic groups in the country.

[3] For instance, a geography degree at Oxford, as taken by Prime Minister Theresa May, costs non-EU students close to £25,000 a year.

[4] All education providers sponsoring international students to come to the UK are now required to apply for ‘highly trusted sponsor’ status. To gain this status, they have to meet criteria that include a high rate of students completing courses and low rates of students having their visas refused. Between May 2010 and October 2014, no less than 836 education providers unable to do so had already lost their licences.

[5] Not to impede the brain drain too much, the government did launch an “exceptional talent” immigration route for up to 1,000 migrants a year who have “won international recognition in scientific and cultural fields” or have the potential to do so.